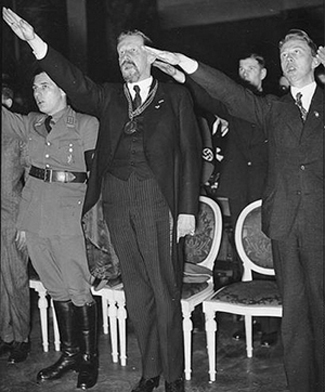

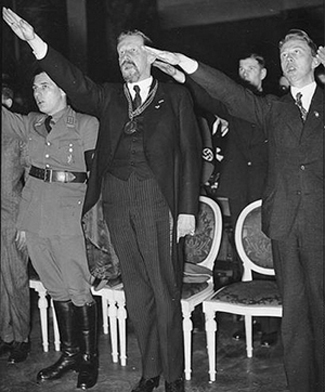

Eugen Fischer (5 July 1874 - 9 July 1967) was a German professor of medicine, anthropology and eugenics. He was director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics between 1927 and 1942. He was appointed rector of the Frederick William University of Berlin by Adolf Hitler in 1933, and later joined the Nazi Party.

In 1905, Fischer's study, "Anatomical studies of the soft tissues of the head of two Papuans" was referenced in Christian Fetzer's study of skulls and possibly brains of Herero and Nama prisoners of war. Fetzer received the 17 heads from Dr. P. Bartels, a physician at Shark Island Extermination Camp1

In a 1906 paper, Fischer was described as professor at the University of Freiburg.

In 1908 Fischer traveled to German South-West Africa himself to conduct field research. He studied the "Rehoboth basters", offspring of German or Boer fathers and African women in Rehoboth, present-day Namibia. He argued that while the existing mixed-race (Mischling) descendants of the mixed marriages might be useful for Germany, they should not continue to reproduce. Fischer's recommendations were followed, and by 1912 interracial marriage was prohibited throughout the German colonies.2

He founded the Society for Race Hygiene in Freiburg in 1908.

Fischer resumed his "bastard studies" at the end of World War I, with the Rhineland bastards (offspring of German mothers and Black fathers), continuing through the beginning of the Third Reich. Fischer was prolific, for he was simultaneously working with American eugenicist Charles Davenport at the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations (IFEO).

Eugen Fischer was recommended for the directorship of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics (KWI-A) by Erwin Baur circa May 20, 1926.3

"The [Kaiser Wilhelm Gesellschaft] senate founded KWI-A at Ihnestrasse 22/24 in Berlin-Dahlem, with Eugene Fischer director, in 1927 (during the "5th International Congress for Genetic Science", led by Erwin Baur) ... Congratulations were also extended to Charles Davenport at this time.4 The new institute inherited the skull collection of Rudolf Virchow and Felix von Luschan.5 The custodian of the skull collection was Hans Weinert, also responsible for paleoanthropology and blood group research.6, 7

When Fischer was appointed the Director of the Institute, Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer was simultaneously appointed as director of Department of Human Genetics. A few years later (1933), Adolf Hitler appointed Fischer rector of the Frederick William University of Berlin, now Humboldt University.8

"The new institute, as Eugen Fischer had announced proudly, would no longer occupy itself with mere skull measuring. In the sense of opening up anthropology toward human genetics, which Fischer outlined with the catchword of anthropo-"biology", the conventional, static, taxonomically organized concept of race that proceeded from morphological features was to be abandoned in favor of a dynamic concept of race conceived in terms of evolutionary biology and grounded in genetics. [...] It could be applied to a multitude of topics, practically all anatomical, morphological, physiological, pathological, and psychological features and characteristics -- "from the dimensions of the skull measurements, structure of spine, red hair, the shape of the ear, the pattern of fingerprints, hemogram, or disposition to tuberculosis, all the way to conceptions of morals, criminality, performance in school or talent for playing chess."9, 10

Twin research was considered to be a window on genetics. It was assumed that the environment affected both identical (homozygote) twins in exactly the same way over an extended period of time. Unfortunately, there was no evidence that this was a sound assumption. The evidence was lacking because the assumption is not true. For example, a mutation could affect the development of one of the twins early in their gestation and not affect the other. "These critical theoretical weaknesses in twin research, which were recognizable in principle even considering the state of knowledge at the time, raise the question as to why Fischer and Verschuer oriented the new institute to assymmetrically toward this methodology."11

A great deal of emphasis was placed on on Twin studies, with Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer and his staff (Karin Magnussen and Josef Mengele) assuming the leadership in this area of work. During the first years of World War II, Fischer worked with Verschuer to transition the main focus of the work from twin study to Phenogenetics.

"The fact that the question guiding research has been so narrowed certainly had something to do with the philosophies of race hygiene and race anthropology at the time - albeit not so much in the sense of conscious, biopolitical instrumentalization of human genetic research as in the sense of an unconscious incorporation of pre- and extra-scientific interests and mentalities into the conceptualization of research."12

Twin research was useful because "...the focus of biopolitical interest could be proven more or less at will. [...] [Christoph] Mai characterizes twin research as a pseudoscience."13

"If we simply cannot reduce costs any further, if we arrive at conditions similar to those during the war, if these persons can, in fact, no longer be held in compliance with human dignity - whereby no only food, drink, housing, and hygiene, but also medical treatment must be considered -, then arises the serious, absolutely burning question for us, what can happen to curtail the burden of heredity."14

"Consequently, in a roundabout way, Fischer opened up the alternative between either minimizing the expenses for closed care to below the existential minimum - and thus triggering mass mortality behind the institutional walls as during World War I - or continuing along the path to opening up the institutions, but then supplementing the open care for the mentally ill, mentally handicapped, and epileptic with eugenic prophylaxis - completely: by means of a sterilization program."15

"Fischer skillfully advanced the argument that there was no longer such a thing as natural reproduction in modern industrial society. Rather, this phenomenon was subject to the constraints of economic relations, so that the hard economic necessity of women's labor compels 'birth control,' but that this takes place 'entirely without plan and without any sense or consideration for the health of the nation and the future.' As such, a 'rationalization of births' was indeed necessary."16

The Hadamar Clinic was a mental hospital in the German town of Hadamar, which was used by the Nazi-controlled German government as the site of Aktion T4 (the Nazi euthanasia program for the 'incurably sick').

In its early years, and during the Nazi era, it was strongly associated with theories of eugenics and racial hygiene advocated by its leading theorists Fritz Lenz and Eugen Fischer, and by its director, Otmar von Verschuer. Under Fischer, the sterilization of so-called "Rhineland Bastards" was undertaken. Grafeneck Castle was one of Nazi Germany's killing centers, and today it is a memorial place dedicated to the victims of Aktion T4.

"By this time the KWI-A had been integrated into Nazi Jewish policy on the practical level as well. A number of staff members produced 'genetic and race science certificates of descent' (erb- und rassenkundliche Abstammungsgutachten) for the 'Official Expert for Race Research' (Sachverstandiger fur Rassenforschung), Achim Gercke, and from March 1935 on for the Reich Office for Geneaological Research (Reichsstelle fur Sippenforschung), renamed in November 1940 to the 'Reich Ancestry Office' (Reichssippenamt) in the Reich Ministry of the Interior. In the 1935/36 fiscal year, as mentioned above, Fischer and Abel supplied over 60 of such certificates ...'17

Limpieza de Sangre literally means "purification of blood". The Probanza de Limpieza de Sangre ("certification of purification of blood") were developed during the early Spanish Inquisition to establish "raza" or race or lineage. They were used to establish "blood" ties to converso (converted Jews) or morisco (converted Moslems) ancestors. They were also used to show blood ties to castas (mixed-blood lineages). Though this is a "negative" view of how limpiezas were used, they were also used "positively", to show descent through noble blood lines. Thus, the concept of race originated circa the 14th century, roughly five hundred years earlier, in the Iberian peninsula, and was a precursor to the 'scientific' activities of Eugen Fischer and others. For further information, click here.

Gunther Brandt (accessory to murder of foreign minister Walter Rathenau in 1922) said that "the director of the institute [Fischer] is 'spiritually a nationalistic man through and through, 'who would 'soon [...] be entirely pervaded by the National Socialist spirit [...] if he were only influenced properly.'"18

"That Fischer yielded to the pressure of his political patron and made active efforts to join the [National Socialist] party from mid-1938 on was probably also a matter of calculation, and closely connected with his plans for reorganizing the institute, which were not to be realized without strong political cover. [...] Reichfuhrer SS Heinrich Himmler, when asked for an opinion by the staff of the office of the Fuhrer's deputy, offered support for Fischer and Lenz in 1938 ... "19 Ultimately, with additional backing from Bormann, Fischer officially became a Nazi on 12/12/1939.20

Even though Fischer did not officially join the Nazi Party until 1940, he was influential with National Socialists early on. A two-volume work, "Foundations of Human Hereditary Teaching and Racial Hygiene", co-written by him, Erwin Baur and Fritz Lenz, served as the "scientific" basis for Nazism's attitude toward other races.21

He authored "The Rehoboth Bastards and the Problem of Miscegenation among Humans" (1913) (Die Rehobother Bastards und das Bastardierungsproblem beim Menschen), a field study which aimed to determine whether human heredity followed the Mendelian laws by studying the interbreeding of two very different human races, Europeans and Africans, in a small population (3000 individuals) whose family history was well known. Fischer demonstrated that such interbreeding did not result in a new, intermediate race that was reproductively stable, but rather followed the Mendelian laws, according to which each generation would produce throw-backs to the original parent races as well as individuals of intermediate type, in the proportion A + 2AB + B, where A and B represent different alleles of a single gene. Although it is sometimes falsely claimed, for instance, in the "Holocaust Encyclopedia" p. 420, that Fischer's study of the Rehoboth Bastards provided context for later racial debates, influenced German colonial legislation and provided "scientific" support for the Nuremberg laws, it was in fact a work of legitimate physical anthropology, without any element of racialist ideology.22

In the years of 1937-1938 Fischer and his colleagues analysed 600 children in Nazi Germany descending from French-African soldiers who occupied western areas of Germany after World War I; all children were illegally subjected to compulsory sterilization afterwards.23

Antisemitic asides in Fischer's private correspondence provide evidence of his antisemitism. He was a racial antisemite, regarding the "Jewish question" as a "question of race". His answer to this "question of race" turned out to be more differentiated than that of the Nazi party ideologues. Losch's statement that Fischer was "no anti-semite", but rather a "racist", misses the point.24

"The Jewish question was in practice the most pressing race question for the German nation, because the Jews were the only people of a strange race who lived within our volk in large numbers. The awareness of a separation in terms of blood, however, did not by any means exclude personal association with individual Jews. [...] Even within the race hygeine movement I had sustained friendly relations in Berlin to the Jewish ophthalmologist Dr. Czeillitzer and undertook a joint scientific project with the Jewish serologist Schiff. This did not deter me from seeing the dangers that threatened the German volk as a whole from Jewry. I received themost flagrant impressions of this from my years in Berlin from 1927-1933, where one encountered Jewry at every turn in the economy and in cultural insttutions and could always feel its close link with the rampant corruption prevalent at the time. The volkish and racial separation between Germans and Jews thus seemed to me a necessary demand to resolve the emerging difficulties for both sides. Through my scientific work I was at pains to work out the foundations to resolve this issue.25

With Verschuer, Fischer was guest of honor at the opening of the Frankfurt Institute for the Investigation of the Jewish Question in March 1941. The goal of the "total solution" to the "Jewish question", was bluntly stated there, as the "Volkstod" ("death of the nation").

In 1944 Fischer and the theologian Gerhard Kittel published a book about "world Jewry of antiquity", a selection of ancient sources with an antiemitic perspective.26

"Publicizing German medical atrocities could undermine wholesale public confidence in clinical science." To avoid the appearance that the entire medical community could no longer be trusted, the Nuremberg Medical Trial political appointees "... presented medical researchers as having been 'perverted' by the manipulative control of the SS and as poisoned by Nazism..." and instead that "the human experiments were so ill-conceived as not to be worthy of the status of science..."27

"[T]he authorities considered that further investigation of hospitals and universities was undesirable, ... [because] if undertaken on a large scale it might result in necessary removal from German medicine of large number of highly qualified men at a time when their services are most needed."28

Thus, the ties of the German medical community — especially those at Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes — were not in any way associated with the death camps; therefore, medical science and the scientists should really be acceptable to the German public and the rest of the world. The SS, and medical personnel such as Mengele who were directly involved with the death camps, were fingered as the most responsible for the atrocities of National Socialism.29

Eugen Fischer served as the head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics until 1942, when he handed over the directorship of the KWI-A to Otmar Frieherr von Verschuer. Fischer returned from Frederick William University of Berlin at the same time. He was made an honorary member of the German Anthropological Society in 1952.

Thus, Eugen Fischer returned to his home town of Freiburg im Breisgau, where he continued to work as an anthropologist.